CLEAN, SOBER, AND GOOD FOR BUSINESS

Ex-substance

abusers power Omni's telemarketing

By Ed Leibowitz in Los Angeles

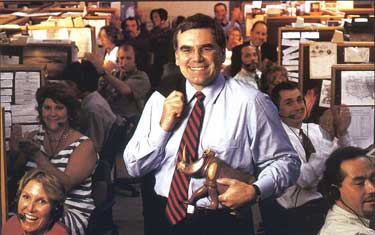

When he's searching for salespeople, Omni Computer Products President

Gerald W. Chamales turns to some unusual recruiters: parole and probation

officers, social workers, and recovery program mentors. He knows their referrals

will have histories of addiction and sometimes nonviolent crime, which can punch

big holes in a resume. But to Chamales that represents potential, not problems.

"They're coming out of a desperate situation, and that's what we look for:

people who are desperate to change their lives. They tend to work harder to

prove themselves," he says. Chamales, 46, speaks from experience. He's a

recovering drug and alcohol abuser himself who bottomed out as a homeless youth

on the streets of Venice, Calif., 25 years ago. From the company's beginning he

has made hiring the hard-to-employ--and managing them with the tenets of

recovery programs--a key part of Omni's corporate strategy.

Today, a third of

his 120 telemarketers fall into this category. They have helped build Omni from

a startup--launched 19 years ago in Chamales' Venice Beach apartment with $1,300

borrowed on a credit card--to a 280-employee national supplier and manufacturer

of Rhinotek-brand printer cartridges, paper, and related products.

Chamales

estimates the privately held company, which occupies 40,000 square feet in

Carson, Calif., grossed $28 million last year, with sales to such blue-chip

clients as Walt Disney Co. and Federal Express Corp. Omni doesn't alert clients

to its hiring policies, but it doesn't hide them, either, and no one seems to

mind. Some sales agents even discuss their personal struggles with

customers.

It turns out that a life hustling on the streets can be good

training for telemarketing. Chamales says these workers are unusually

persuasive--a useful skill when you're making 25 to 30 cold calls day.

The

results surprise even Stephen Marcus, a California judge who heads a court-run

rehab program from which Chamales has hired. "Hard as it is to believe, these

people are good workers," Marcus says.

It is, indeed, surprising. Addicts and

alcoholics cost the economy $314 billion a year just from absenteeism, not to

mention any hidden damage their performance does to their employers. The

difference at Omni is that people don't have to cover up. "An employer who hires

recovering people is hiring people who acknowledge they have a problem, and some

of those costs could be avoided," says Scott Robertson, administrator at

Glendale Adventist Alcohol & Drug Services, in Glendale, Calif.

Managing

those workers is no simple matter. It takes special supervisors to do the job.

Take Joe Hiller, senior vice-president of sales. He came to Omni in the summer

of 1984--40 days sober after more than a decade of substance abuse--decked out

in his father's ill-fitting suit. "I didn't even know how to tie a tie," says

Hiller. His first check, commission only, was $27. Within a year, he had moved

into management.

RECOVERY ZONE

Managers at Omni Computer Products

use some unconventional techniques to tap the talents of ex-addicts and

alcoholics. Here's how they do it:

View recovering employees as long-term

investments: Some will suffer setbacks. Others need to deal with legal,

health, or family problems caused by past drug abuse. Be flexible.

When

hiring, set sobriety standards and screen intensively Prospects should

demonstrate 30 days' sobriety and participation in a recovery program. Probe

commitment to change with multiple interviews and written tests.

Provide

in-house mentors: Mentors offer reassurance and discipline to newly employed

and sober workers. Ex-substance abusers often need counseling on basic social

and workplace skills.

Be open with outsiders: Turn your dedication to

recovering workers into a selling point. Most people have a friend or relative

undone by drugs or alcohol. That offsets the stigma attached to

addiction.

HONOR SYSTEM.

Before Chamales will hire anyone with a

troubled past, he demands 30 days of sobriety in a treatment program. He forgoes

drug tests, relying instead on his own instincts and the honor system.

Applicants are given a 50-question multiple-choice test to detect qualities

associated with Omni's top sellers and to help weed out "50-yard-dashers,"

smooth talkers who won't last. The company actually has an incentive to hire the

ex-felons--a credit of up to $2,400 on their first-year salary under the federal

Work Opportunity Tax Credit Program.

Once hired, telemarketers learn the

company's well-defined rules. Although they don't visit clients, sales

agents--all of whom get 5% commission and earn $250 to $400 per week for the

first year--have to dress professionally. "We come here broken or limping, and

the company shows us the path," says Alan Jacob, 49, once a heroin addict, now

vice-president of sales management. "There are a lot of guidelines and structure

here because we need that."

Managers balance that strictness with sensitivity

to personal problems that can mar performance. To help employees restore credit

or finance a car, for instance, Omni has disbursed $250,000 in loans. Another

technique is to assign a mentor to each new employee. Ex-addicts often need help

with such basic etiquette as shaking hands. "Twenty years ago, I had trouble

looking into people's eyes," admits Chamales, who was raised in foster homes and

started drinking at 14. And mentors help ease the emotional roller coaster of

commission sales itself, which can take a toll on anyone.

How do employees

from the regular workforce feel about their ex-addict colleagues? "They can be

more sensitive," says Judy Vallembois, the Sales Administration Manager,

misinterpreting even routine brusqueness as harsh criticism. But "they're a lot

more creative and more fun to be around."

All this support results in lower

turnover, especially during the first year, when the telemarketers are earning

the least for the company. Among Omni's rehabbed workers, the first-year

retention rate is 15%, while only 8.5% of those from Omni's regular workforce

are left after 12 months. Such attrition would be dismal in most businesses, but

experts say it's quite solid for telemarketing..

Workforce longevity makes

other savings possible. Many telemarketers rely on sophisticated

customer-contact software, which costs from $3 million up to $25 million, for a

300-seat call center. These systems provide more background data than Omni's

long-term account executives need; they have much of it in their heads. Omni

didn't bother upgrading its antiquated DOS system to Windows until last

year.

Omni's rehabilitating mission works for high-level recruitment, too.

Earlier this year, Chamales began introducing a retail Rhinotek line. To lead

the push, he hired David Bleeden and Jerry Dix. Bleeden is a recovering addict

and co-founder of Naked Juice, a startup acquired in 1987 by Chiquita Brands

International Inc. Dix lost his share of a $19 million lug-nut business because

of substance abuse. Chamales says that under other circumstances, he wouldn't be

able to hire executives with that pedigree.

To be sure, not every day is

sunshine and success. Chamales weathered two death threats 10 years ago. A bomb

scare five years ago shut operations for half a day, causing about $50,000 in

lost sales. And $25,000 in supplies evaporated some years ago. He has identified

only one of the culprits--a rehab worker whom he had fired. EARLY SIGNS. The

more common problem is relapse. Omni mentors know the early signs: absences,

tardiness, bizarre behavior, a lack of focus, two-hour lunches. Six months ago,

Hiller, Chamales, and mentor Carole Garland stepped in when Kelly McFadden, 32,

started drinking again after 4 1/2 dry years. After talks and two sick leaves,

Hiller says, "we got to the end of our rope. She was coming to work drunk,

spilling food, telling us she had cancer." They gave her an ultimatum: rehab or

termination. Omni helped her find a treatment program, and colleagues covered

her accounts, so she wouldn't come back broke.

Some might read this as a

cautionary tale. Not Chamales. "Kelly is one of our very solid, top-producing

executives," he says. "To find one of her caliber is not easy." Back at work

after a few months, she tries to convey her appreciation: "This is my home, my

family."

Chamales has ambitious plans for his workers. "Two hundred twenty

million in gross sales by 2002," Chamales says. "That's the big hairy goal." And

if that expansion causes stress, not to worry: Omni's new call center has a

discreet, well-lit counseling room.